“That stranger, Pete McCann—funny that none of the adults know him—he’s made a lot of records. He gave a folk singing concert at school just last night. He’s been way out all day. I suspect he’s going to be trouble.”

--Jeannie Howard to her Fallout Shelter Diary in the civil defense film Public Shelter Living: The Story of Shelter 104 (1964)

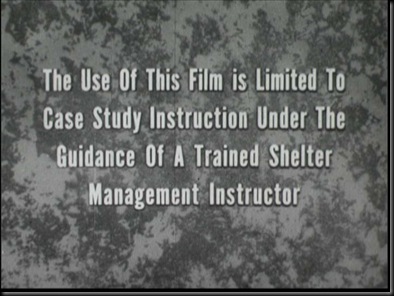

“The Use of This Film is Limited To Case Study Instruction Under the Guidance Of A Trained Shelter Management Instructor.”

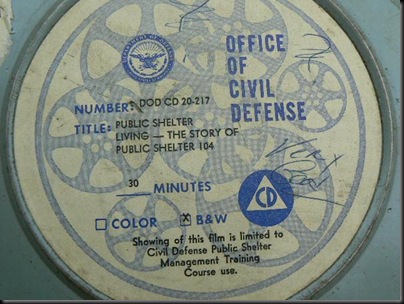

--Disclaimer at the beginning of Public Shelter Living: The Story of Shelter 104 (1964)

“This was a job and that was just about the end of it. The Army was never very good about telling you the why…”

--James R. Hartzer, the director and producer of Public Shelter Living: The Story of Shelter 104 (1964)

PART I: THE FILM

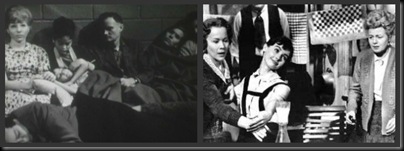

As a result of the National Fallout Shelter Survey and Marking Program that began in 1961, a new subgenre of American civil defense educational film was born—the Public Shelter Occupancy movie. Examples of this cinematic form include Information Program Within Public Shelters (1963), Occupying a Public Shelter (1965) and the movie to be examined in this post, Public Shelter Living: The Story of Shelter 104 (1964).

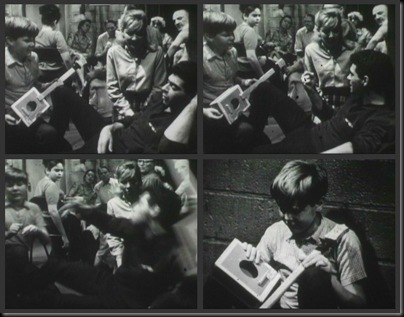

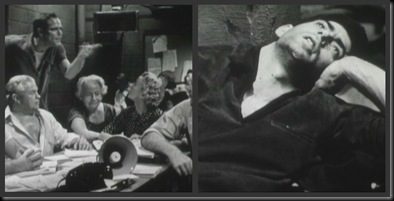

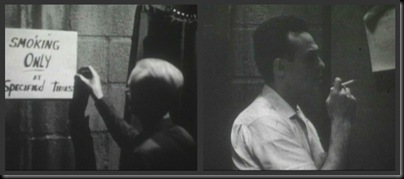

Of the three works, Shelter 104 is the most interesting because of the unique and bizarre (for a government training film) counter-cultural conceit of the story. Specifically, the anonymous screenwriter decided to inject a cynical, folk-singing beatnik into the standard issue mix of worried-yet-obedient shelterites. Regardless of the fact that this malcontent will ultimately be converted to the pro-survival cause, his negative, slang-slinging presence is what makes this movie a genuine classic.

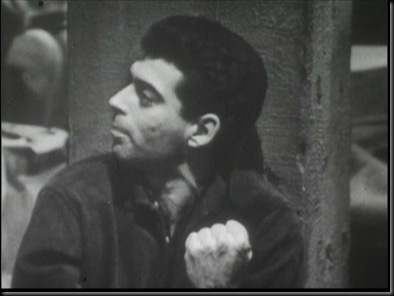

“Pete McCann,” who appears approximately ten minutes into the half-hour film (the shelter manager permits his belated, post-attack entry after a police officer explains, “I found this character in the street getting drunk’) wastes little time in belittling the earnest efficiency of the tie-wearing shelter management team:

Contemplating your errors, friends? You know, the fact is, you made a stinking mess out of everything. And now we’re all going to die down here in this black little hole.

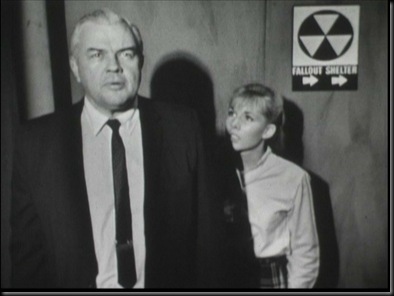

But McCann’s scorn is not targeted solely at the establishment elders – he shoots his nihilistic daggers at everyone, including a perky blonde college student named Jeannie Howard. Jeannie, who keeps a chatty diary that remarks on how the rations of survival biscuits and orange drink help “say goodbye to extra weight the shelter way,” is the optimistic counterbalance to the dark and brooding McCann.

The viewer knows from the start that it is only a matter of time before Jeannie’s peppiness carries the day, but it is the conflict between these two polar opposites that keeps us watching. When Jeannie observes McCann sulking (or withdrawing from heroin?), the following dialogue ensues:

Jeannie: The world didn’t end this morning, Mr. McCann. It’s still here.

McCann: Now, it’s not really a world we can live in, is it?

Jeannie: We really don’t know about that, do we? I mean who can say?

McCann: Don’t give me a lecture on the survival of the species, little girl. The species is a flop. And whether it all goes up in one grand whoosh or carries on for another week or drags on for a month… [McCann’s diatribe is interrupted by another shelter dweller who yells at him to “shut up.”]

A little later, when Jeannie tries to give McCann a reality check after he complains about his guitar being stolen the previous evening, he makes a fist and says:

You know, you’re a regular little Salvationist, aren’t you? You’re all fitted up with your power of positive thinking.

But the indefatigably sunny Jeannie won’t give up and conspires with a young orphan boy named Jeff to present McCann with a makeshift guitar (and a plea to entertain their fellow survivors). Before throwing the instrument across the shelter, the beatnik sneers and says “The whole world is going down the drain and we want a little music.”

McCann’s black cloud rubs other people in the shelter the wrong way, too. In one heated moment a shelter resident points at the morose folkie and declares “I’ll tell you what’s spoiling the atmosphere around here – him! – and I think we ought to send him for a little walk.”

McCann’s turning point comes when he realizes—with Jeannie’s help (she’s the daughter of a doctor who may or may not have been atomized in a neighboring town)—that he isn’t dying of radiation poisoning, but is merely suffering from a reoccurrence of his allergies (the out-of-it beatnik laughs as he remembers he offered his bottle of Benadryl to the shelter manager upon his drunken entry several days before).

Jeannie wastes no time in unloading on the suddenly relieved and life-loving McCann:

There’s something I want to tell you. You’re a liar—to yourself and everyone in here. You don’t want to die any more than we do. The way you’ve been carrying on with your superior attitude and phony cynicism. But when the chips are down, when you thought you were sick with something you could put your finger on – like a germ or scarlet fever, not something invisible and mysterious like radiation, you dearly want to live, don’t you?

After McCann slightly nods, the co-ed concludes her emotional speech:

Well fine. I suppose that makes you a member of the human race, after all. And since you’re in the club, Mr. McCann, and really don’t want to leave us just yet, the least you can do is pay your due.

The film concludes with a now smiling Pete McCann strumming the reconstructed, but somehow longer-necked guitar that he had destroyed earlier. The wildly appreciative shelter audience appears to dig the pro-survival message of McCann’s presumably new folk composition. The unlikely lyrics—“No more fears and no more talk of dying / we’re going to spread the word…”—fade out over the Department of Defense and Army Pictorial Center end titles.

PART II: THE MAN WHO MADE SHELTER 104

When CONELRAD first saw the civil defense masterpiece described above we wanted to try and track down the actor who had played the role of Pete McCann with such surly finesse. We are still looking for the elusive Fallout Shelter beatnik, but we did manage to locate the man who directed and produced Shelter 104 —James R. Hartzer.

Hartzer, now in his seventies, confessed to being “stunned” about our inquiry, but was more than happy to discuss what was, in fact, his very first movie. The retired filmmaker and businessman explained to CONELRAD’s Bill Geerhart that he knew from his early teenage years that he wanted to work in television. “I knew I was going to New York to direct television.” And, to that end, the young man spent his college summers pushing a broom as a custodian at Chicago’s WGN-TV (it was close as he could get). After graduating from DePauw University in Indiana in 1959 and after some graduate work at Michigan State, Hartzer bluffed his way out of a possible forward position in Vietnam and into a slot with the Army Pictorial Center in Astoria, Long Island City, Queens, New York. It was where he was meant to be.[1]

Hartzer recalled that it was literally his first day on the job in late 1963 when a superior called out to the assembled workforce: “Does anyone here know how to switch [cameras]?” The aspiring young director brashly volunteered and offered that he had “worked at WGN.” By omitting the janitorial nature of his position at the station, Hartzer had satisfied the higher-ups that he knew what he was doing. He was immediately handed the screenplay for Public Shelter Living: The Story of Shelter 104 and ordered to shoot it.

“I’m sorry to say, I don’t remember who wrote the script,” Hartzer told CONELRAD, but added that he did not change it. “I thought it was very good and whoever wrote it had done a great job on it.” With regard to the folk song that concludes the film, Hartzer allowed that the lyrics may not have been in the screenplay and that the tune may have been recorded later.

The set for Shelter 104 had already been built, so Hartzer concentrated on casting the movie. The Army Pictorial Center had a casting department that arranged auditions based on the criteria producers provided to them. According to Hartzer, officers would frequently attend these try-outs and occasionally attempt to dissuade him from choosing a particular actor. Hartzer stated that he always stuck to his guns and went with the performer he thought could best carry off a role. With regard to Pete McCann, the star character of Shelter 104, Hartzer could not remember the actor’s name, but agreed that he brought a memorable intensity to the part.

When asked about whether he looked to any outside inspiration for creating the fearful, claustrophobic mood of shelter life for his movie, Hartzer said that he had the 1959 movie version of The Diary of Anne Frank in mind.

The young director was aware of the controversy surrounding civil defense at the time he was preparing to film Shelter 104, but he was agnostic about its efficacy. As Hartzer explained in his interview, any opinion he might have held on the issue would not have mattered much. “This was a job and that was just about the end of it. The Army was never very good about telling you the why. We shot the film in a week or two television style and it was converted to 16mm (Kinescope).”

Hartzer edited the film with a skilled professional named “Jerry” who later went to Hollywood to work on major studio motion pictures.[2] On the afternoon of November 22, 1963 Hartzer and Jerry took a short break from their work when President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas. A few hours later, they were told by the Army to get back to work. When it was all over and the film was in the can, Hartzer remembered that “I was just pleased to get though it.”

The director worked on many other training films during his stint in the service and it wasn’t until his superiors were trying to get him to reenlist that he paused to think back to his first project. “Whatever happened to that film?” he asked of one of the people lobbying him to re-up. It was at this point that Hartzer discovered the surprising fate of Shelter 104. “Once these training films were completed,” Hartzer explained to CONELRAD, “they were sent down to Washington. Some colonel liked it and had it submitted at Cannes.”

Representatives of the Cannes Film Festival did not reply to CONELRAD’s request for additional details, but in the 1967-1968 edition of the Directors Guild of America Directory, the entry for James R. Hartzer states that the film was submitted to Cannes in 1964.

James R. Hartzer went on to work on numerous other film and video projects as a civilian, mainly in an executive capacity, but he still has a 16mm copy of Shelter 104 in his Connecticut home. He has not watched it since it was completed nearly a half century ago, but he told CONELRAD that it still occupies a special place in his heart.

APPENDIX: GOVERNOR DERWOOD O. AMBACHER’S POST-ATTACK RADIO ADDRESS

Just before Pete McCann’s dramatic entrance into the shelter, the shelter occupants are listening to a radio address by their fictional governor. The following is the text.

Radio Announcer: Attention please. This is state civil defense headquarters. Stand by for an important broadcast. The next voice you hear will be that of the honorable Derwood O. Ambacher, governor of our state.

Governor Ambacher: My fellow Americans: Those of you who hear my voice already know that this nation has been attacked with nuclear weapons. At this time, we cannot estimate the extent of damage already done. I have been in contact with…

At this point a banging on the shelter door is heard and the action shifts away from the radio, but it is also made clear that Ambacher’s address has terminated for some unknown reason.

CREDITS (Incomplete)

Public Shelter Living: The Story of Shelter 104

DoD CD 20-217

Army Pictorial Center in Cooperation with Staff College Office of Civil Defense

30 Minutes

Black and White

Director / Producer: James R. Hartzer

Written by: Unknown

Edited by: Jerry (surname unknown)

CAST (Incomplete)

Pete McCann: Unknown

Jeannie Howard: Unknown

Mrs. Howard: Unknown

Bob Hassler: Unknown

Mr. Pitts: Unknown

Jeff: Unknown

Police Officer: Unknown

Mrs. Starr: Unknown

Mrs. Sugarhouse: Unknown

Herb, Shelter Manager Assistant: Unknown

Mr. Brewer: Unknown

Annoyed Young Male Shelterite: Unknown

Radio Announcer (Voice Only): Unknown

Governor Derwood O. Ambacher (Voice Only): Unknown

REFERENCES

Interview with James R. Hartzer conducted over the telephone by Bill Geerhart on July 2, 2011.

Directors Guild of America, Directory of Members, 1967-1968, pp. 129-130

ADDITIONAL READING

Public Shelter Living: The Story of Shelter 104 was used as part of an unusual shelter occupancy study in 1965. To read more about it, see our Survival Vérité post.

[1] Having completed his education, Hartzer decided to enlist and get Army-financed film training with the Signal Corps. His other option (in 1963) was to be drafted into military service.

[2] CONELRAD reached out to the Army Pictorial Center history website for assistance in identifying “Jerry” and they have graciously posted a “Help” item on their front page.